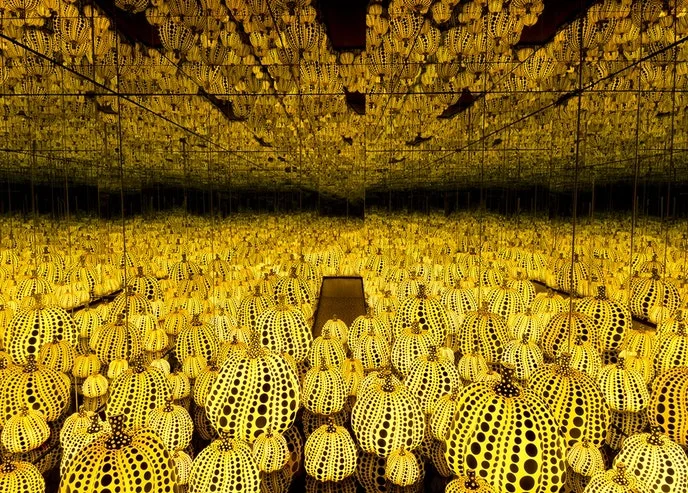

When Yayoi Kusama moved to the United States in 1957, age 28, she was an ambitious young artist weary of the conservatism and discrimination she faced in her native Japan. She settled in New York, quickly becoming part of the avant-garde art scene, where she developed her several signature motifs. She loved brightly colored polka dots, sometimes covering an entire painting, wall, or room with them so that the polka dots obliterated the underlying support. She created mirrored rooms with suspended colored lights which made visitors feel they were part of an ethereal infinity. She also created large, monochromatic paintings called infinity net paintings filled from edge to edge with painted loops. The simple act of painting loop after loop created surprisingly complex paintings that seemed to have different points of tension as viewers scanned their surfaces.

These works, which she has consistently produced over more than five decades, were not always a commercial success. Today, she is one of the few women who consistently rank among the highest-selling living artists by sales volume and value. What accounts for her present popularity, and what does it tell us about the art market? Her partnership with consumerism is an important factor behind her career renaissance, but her work is also uniquely suited for our Instagram age. Her journey runs from downtown New York to Japanese mental hospital to the windows of Louis Vuitton boutiques and beyond.

THE FAME-HUNGRY, ANTI-WAR NEW YORK WORKAHOLIC

In 1959, Kusama showed five large infinity net paintings in her first New York exhibition. Each was composed of thousands of individual white loops painted on a black ground. Donald Judd, who at the time worked as an art critic for ARTnews, wrote in his review that “Yayoi Kusama is an original painter. The five white, very large paintings in this show are strong, advanced in concept and realized.” He went on to say “The expression [in the paintings] transcends the question of whether it is Oriental or American. Although it is something of both, certainly of such Americans as Rothko, Still and Newman, it is not at all a synthesis and is thoroughly independent.” It was high praise from a curmudgeon.

Kusama was a workaholic. Moreover, she was obsessed with being noticed and recognized; she hungered to be famous. She found her way to the center of the action, be it people, parties, or performances. Because she created provocative work for the time, it was easier for her to be noticed. She covered tables, chairs, and shoes with phallus objects she made of silver-painted stuffed canvas. She also organized naked anti-war happenings, including one on the Brooklyn Bridge, where participants stripped down and Kusama painted them with polka dots.

SURVIVING AND WORKING THROUGH MENTAL ILLNESS IN JAPAN

After fifteen years in the United States, Kusama moved back to Japan in 1973. She had a history of recurring psychiatric problems. When her issues became particularly acute in 1977, she elected to admit herself to the Seiwa Hospital for the Mentally Ill in Tokyo. She continued as an active artist, going to a nearby studio to work and returning to the institution for meals and treatments. But the art world is a tough place: out of sight, out of mind. She fell off the radar, reduced to an interesting footnote in the history of the 1950s and 1960s New York art scene.

She gained noticed again in the early 1990s, when she represented Japan at the 1993 Venice Biennale. Her work slowly appeared once more in gallery shows in New York, London, and Los Angeles. By the middle of the last decade, her career had accelerated, with important galleries in Europe and the United States representing her. Her rise coincided with a surge in Asian wealth and collectors there wanting to own her work. Important museum shows followed, including a major retrospective in 2011 and 2012 that traveled to the Whitney Museum in New York, the Tate Modern in London, the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, and the Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid.

PERSONAL NARRATIVE, HIGH PRODUCTION, AND SOMETHING FOR EVERYONE

Personal narratives are sometimes an important factor behind collectors buying an artist’s work. This is especially true for Kusama. I remember one conversation with a young collector couple about the artist. I asked them, “Why Kusama?”

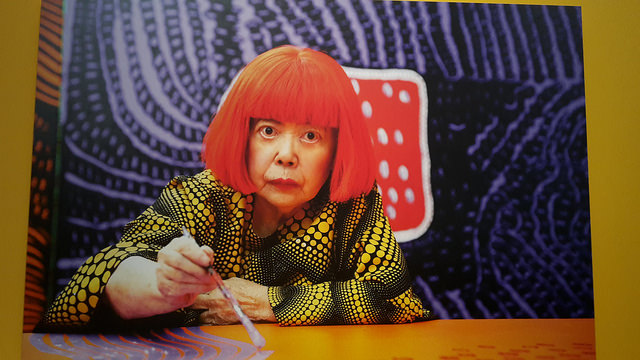

Without hesitation, they said something along the lines of, “She’s badass. She does her own thing. She stayed true to herself and makes no apologies for it. She thumbed her nose at the world and waited for the world to come to her.” The visual and the emotional merged for this couple, who bought the highest-quality work they could afford at the time, a drawing from the early 1960s. Stories about Kusama’s mental health issues and her fierce determination and longevity help some collectors understand her work and explain it to their friends. She still craves attention and dresses to remain unforgettable, wearing bright red wigs, outfits covered with polka dots, and goes about in a polka-dot encrusted wheelchair.

As her popularity increased, so did her production. She started using studio assistants and repeating older themes, especially infinity nets. She created work in different sizes, colors, and media, including new infinity rooms and large pumpkin sculptures. An infinity room at the Broad Museum in Los Angeles is now a major tourist attraction and a destination of choice for selfies. Her work is perfect for Facebook and Instagram.

While conceptual and highly emotional, her work is accessible through its graphic nature and exciting beauty. Collectors across the globe have been drawn to her aesthetic, from the broad appeal of her gallery and museum shows to her installation in a Ginza Tokyo department store this year. Her partnership with consumerism is an important factor behind her career renaissance. She embraced consumer culture to expand her market: her partnership with Louis Vuitton in 2012 dramatically increased awareness of her work and her personal narrative. But her availability penetrates deeper than the market for million-dollar paintings and multi-thousand-dollar handbags. Enthusiasts at a more modest price point can own their own piece of Kusama through licensed key chains, mouse pads, paperweights, and polka dot pumpkin pillows.

The ready availability of her work at different price points helps stimulate demand - an odd case of higher supply generating higher demand. Buyers do not have to search high and low to find something to buy. If they’re unable to get something from one of the galleries that represent her, they can buy something at auction, or at an upcoming art fair, or call around to the numerous galleries that offer her work on the secondary market. Familiarity has not bred contempt, but instead greater interest and demand for her work. Collectors are now willing to pay extraordinary sums for her important early paintings which laid the groundwork for her fully-realized vision today. In November 2014, a white infinity net painting from 1960 sold for a new world record of $7.1 million; ten years ago, it would have sold for a fraction of this amount. For most artists, scarcity rules. But for Kusama, like Andy Warhol, embracing consumerism helped propel awareness and sales of her work.

A version of this article appeared in Artsy on November 20, 2017. Click here.

Doug Woodham is the Managing Partner of Art Fiduciary Advisors, a NY-based firm focused on providing art-related financial consulting to collectors and institutions. Earlier in his career, Doug was President of Christie’s for the Americas and a Partner with McKinsey & Company. He is also the author of the best-selling book Art Collecting Today: Market Insights for Everyone Passionate About Art (2017).