Why It's So Hard to Fake a Rene Magritte

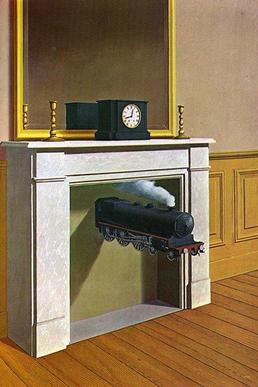

Rene Magritte is the master of the Surrealist image. He’s depicted a gigantic green apple filling an otherwise empty room; shown a train engine with a full head of steam inexplicably barreling out from the center of a fireplace in an ordinary living room. These indelible images have made him the king of the double take, and one of the most popular artists in the world.

Despite his widespread popularity, Magritte is collected in-depth by only a handful of people -- around ten collectors worldwide. Wilbur Ross, the current Secretary of Commerce in the Trump Administration, is the most public about his Magritte obsession. Collectors in this group understand the art historical importance of the artist’s early work and appreciate the linguistic jokes that he often incorporated into his paintings. There’s also a second group of buyers, primarily Western collectors, who are interested in owning something with subject matter that clearly identifies itself as a Magritte. They seek instantly recognizable images because they are only likely to buy one work by the artist, and tend to gravitate towards works that are aesthetically beautiful, or perhaps, as these are mostly male buyers, feature a naked woman.

Regardless of what type of work they covet, Magritte collectors can buy with confidence. They are very unlikely to be offered a fake, not only because the artist has been the subject of an exhaustive catalogue raisonne (as is the case for many other artists), but because since its formation in 1998, the Magritte Foundation has actively engaged with players throughout the art market to ensure that fakes are sniffed out and removed. The Foundation’s ongoing engagement with the market is worth highlighting at a time when many other artists’ foundations and estates are backing away from authenticating work.

BECOMING MAGRITTE

Born in 1898, Magritte spent most of his life in his native Belgium. He fell in love with art-making early, starting art classes when he was about twelve, and attending art school when he turned eighteen. By the time he was 28, in 1926, he had hit on his distinctive style, and continued to paint in this vein until the late 1930s. During this time, Magritte also started a small advertising agency with his brother.

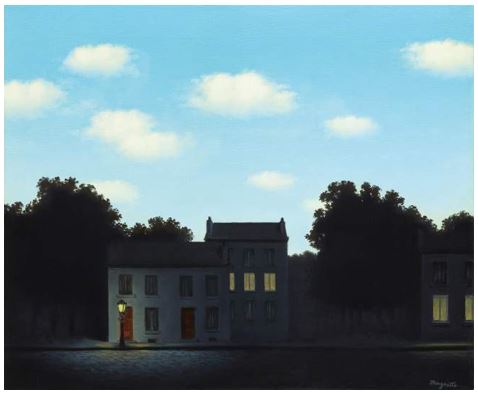

Magritte pivoted away from surrealism in the early 1940s and produced a large body of what many critics have deemed mediocre work. But by 1948, he returned to his surrealist tropes and continued to paint in that style for the next twenty years until he died in 1967. Work from his later period is typically more popular than earlier work because the images are more “iconic.” Sometimes he fell in love with images and painted multiple versions of them, playing around with color, scale, and composition. For example, he painted 27 versions of what has come to be called the “Dominion of Light” series - seventeen versions in oil with ten more in gouache (which is opaque watercolor). The first oil painting in the series sold at auction in November 2017 for $20.5 million, a new world record auction price for the artist.

A THOUGHTFUL AND CREDIBLE AUTHENTICATION STANDARD

Magritte was world famous when he died. But success can breed fakes. In 1969, The Menil Museum and Foundation in Houston provided funding for a catalogue raisonne on the artist. It was twenty-three years before the first volume came out. By 1997, Volume 5 had been published. The catalogue raisonne now includes approximately 1,700 works: around one thousand paintings and seven hundred sculptures, objects, and works on paper. It is an extraordinary piece of scholarship that the marketplace accepts as the authoritative reference on what constitutes a real Magritte.

But no matter how thorough the scholarship, new works turn up. To keep the catalogue raisonne alive, the Magritte Foundation was founded in 1998 in Brussels to safeguard the work and reputation of the artist. The Foundation subsequently created an authentication committee in 2000 to review and render opinions on whether a work is authentic. This seven-member committee, which is comprised of three representatives from the Foundation and four Magritte experts, meets twice a year.

To be considered for review, the owner must send the work to Brussels along with full cataloguing and provenance information. Committee members then inspect the object, evaluate the submitted information, and discuss and debate the merits of the case. The committee charges a fee for their work. If deemed authentic, the owner will receive a certificate from the committee along with any additional cataloguing or provenance information discovered during the review process. A sixth volume of the catalogue raisonne was published in 2012 to document the committee’s decisions.

If the committee does not believe the work to be authentic, the owner is typically informed verbally. The work will then be returned to the owner with no marks or notations made to it (e.g., no stamps or labels saying the work is a fake). The absence of an affirmative document from the committee about an object’s authenticity is what seals its fate. Smart collectors and their advisors know to only acquire work that has been vetted and approved by the Foundation’s authentication committee.

For some time now, major auction houses and top galleries have only offered work by Magritte that is accompanied by a Magritte Foundation authentication certificate (or sold subject to the receipt of one). Even collectors who own a Magritte that is included in the catalogue raisonne, but who bought it before the authentication committee came into existence, still need to obtain a committee certificate if they intend to sell it. Because of these practices, it is very difficult for a fake Magritte to trade in the art marketplace.

AUTHENTICATION SHENANIGANS

Given the accomplishments of the Magritte Foundation, why don’t more artists’ foundations follow in their footsteps? The Magritte Foundation has a key advantage that many other foundations don’t. By virtue of being located in Belgium, it is protected under Belgian law through a legal concept called ‘Droit Moral,’ a French term meaning “moral rights.” It refers to rights that creators and their heirs have to protect the integrity of their work, including the right to render opinions on whether work is authentic. These rights make it extremely difficult for anyone to challenge an authentication opinion rendered by the Magritte Foundation. Unfortunately, the same protections do not exist in the United States. As a result, many artist foundations, including those of Andy Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Keith Haring, have elected to stop providing authentication certificates due to the time, cost, and effort associated with defending themselves against lawsuits challenging their decisions. The United States is still the world's largest art market, accounting for 40 percent of global art sales in 2016, according to UBS and Art Basel's The Art Market | 2017. The entire marketplace would benefit if similar protections were in place in the United States.

A version of this article appeared in Artsy on January 5, 2018. Click here.

Doug Woodham is the Managing Partner of Art Fiduciary Advisors, a NY-based advisory practice focused on art-related legacy planning and advising collectors, artists, and institutions on the sale of art. Earlier in his career, Doug was President of Christie’s for the Americas and a Partner with McKinsey & Company. He is also the author of the best-selling book Art Collecting Today: Market Insights for Everyone Passionate About Art (2017).