Articles by Doug Woodham

A nagging concern for many collectors is what to do with a collection passionately assembled over time, if or when their circumstances change. It’s a complicated question without a one-size-fits-all answer. One of my clients gave me permission to share (on a disguised basis) the integrated plan we created last year for their collection. It serves as an example of what’s involved in creating a pragmatic financial plan for a valuable art collection.

With so many works for sale, a recurring question for collectors is whether galleries or auction houses offer buyers a better deal. Based on my experiences as a collector, art advisor, and former President of the Americas for Christie’s, the answer depends on context and the type of work being sold.

Art museums in the United States live on the generosity of individuals. Most of the financial support they count on for their annual operating budgets come from individuals, or foundations and trusts set up by them.

One accurate cliché of the art world is that nothing matters more than relationships and information. High-end art dealers and auction houses know this better than anyone. How do they acquire these relationships and information?

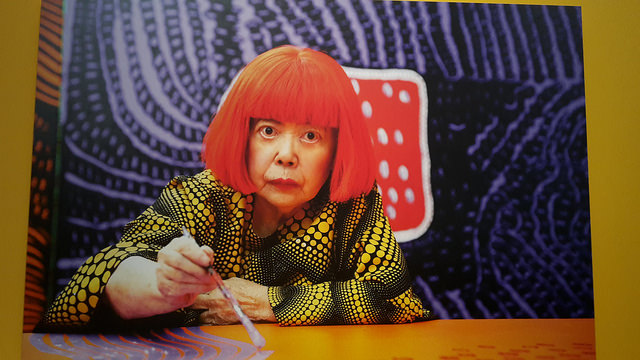

When Yayoi Kusama moved to the United States in 1957 at the age of twenty-eight, she was an ambitious young artist tired of the conservatism and discrimination she faced in her native Japan.

While Andy Warhol believed that “In the future everyone will be famous for fifteen minutes,” the artist retains his fame today almost thirty years after his death. Warhol is, in fact, so relevant to contemporary culture that despite being a thoroughly American artist, laws in other countries increasingly categorize works by the artist as cultural property subject to export restrictions and limitations on sale.

David Rockefeller inherited many things: a storied name, unimaginable wealth, an inquisitive mind, and a profound compulsion to collect. Both his parents had the collecting gene. His father, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., was the only son of John D. Rockefeller, the founder of Standard Oil and one of the richest individuals in American history.

Everyone loves Rene Magritte, the master of the surrealist image. Maybe the first time you saw something by him was when you noticed a poster of a train engine with a full head of steam inexplicably barreling out from the center of a fireplace in an ordinary living room.

Collectors are sometimes terrified to sell works of art at auction—and not without reason. Maybe the object will fail to sell, becoming tainted or “burned” in the eyes of the marketplace. Maybe the estimates the consignor agrees to are too low, and the work sells for a song. But selling at auction also exposes the work to the largest number of potential buyers, increasing the odds it will sell for the best price possible.