Introduction to Jean-Michel Basquiat: The Making of an Icon

My fascination with Jean-Michel Basquiat took root when I moved to New York City in the early 1980s. Though his name was familiar to those of us who followed the contemporary art world, opportunities to see his work firsthand were scarce.

Front Cover of “Jean-Michel Basquiat: The Making of an Icon”

My fascination with Jean-Michel Basquiat took root when I moved to New York City in the early 1980s.

Though his name was familiar to those of us who followed the contemporary art world, opportunities to see his work firsthand were scarce. I was delighted when his name appeared in a New York Times review of a group exhibition featuring four hundred artists. Eager to see his work, I visited the exhibition space—a sprawling, abandoned army depot in Brooklyn. But after wandering through the dystopian venue, I was unable to find any of his pieces. Frustrated, I returned to the entrance and asked the person at the front desk where the work was displayed. I was told that Basquiat’s paintings had been removed due to concerns about theft, as his pieces had suddenly become highly sought after. While my plans to see his work that day were thwarted, my interest in his art only deepened.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, the Brooklyn-born artist who died of a drug overdose in 1988 at the age of twenty-seven, currently stands alongside a handful of others at the pinnacle of what a visual artist can hope to achieve in our world. When one of his paintings sold for $110.5 million at auction in 2017, he joined the exclusive “$100 million club,” alongside luminaries such as Picasso, Modigliani, and Munch. The streets of Rio de Janeiro, Paris, and Singapore are filled with people of all ages wearing T-shirts, shoes, and accessories featuring his art-work or image. Some fans even express their admiration permanently through Basquiat-inspired tattoos, sharing their ink on social media with #basquiattattoo. His cultural impact is so far-reaching that he has become a frequent answer on Jeopardy!

But Basquiat’s ascension into these parallel pantheons of fine art and pop culture was far from certain. Despite starting life with the gifts of a sharp intellect—his family recalled him reading articles in The New York Times by first grade—and a financially stable, middle-class home, he was sidetracked by profound early personal traumas. By his teenage years, he had dropped out of high school and was living on the streets. He was without any formal training as an artist and initially wanted to be a cartoonist. A shy and, in some ways, fragile young man, he also had to face down the challenge of penetrating the elitist con-temporary art world of the early 1980s, where Black artists struggled to find recognition and acceptance.

So how did Basquiat’s work overcome so many obstacles—both during his brief life and after his death—to achieve such critical and commercial acclaim? Like a deity with a broad scope of jurisdiction, he has become a patron saint to many: Basquiat the artistic visionary, Basquiat the truth-telling Black activist, Basquiat the outsider. Yet he was also a real person driven by relatable human motivations.

Since attending that Brooklyn exhibition, I’ve followed Basquiat’s trajectory throughout my career—as a partner at a global management consulting firm; president of Christie’s Americas, the international auction house; and an art advisor to collectors and institutions. What these roles have provided me with is an insider’s view of the forces driving the blue-chip art market, a world often shrouded in opacity, as if its inner workings were best kept behind the canvas. Yet this labyrinthine and occasionally contentious system underscores a broader truth: Understanding how art is valued illuminates why certain artists rise to prominence. Whether one likes to think about it or not, the works that dominate attention and secure pride of place in leading museums and collections have all, at some point, passed a demanding market test.

As I delved deeper into this book, I also came to realize that while Basquiat and I have some of life’s broadest experiences in common—middle-class upbringings in church-going households and a few years’ difference in age—my real connection to him lies in my admiration for his insatiable curiosity, self-directed ambition, and relentless determination to carve out a place for himself in the world. Drawing on my own, albeit very different, experiences in an adjacent part of the art world, along with insights from over a hundred interviews with those connected to Basquiat—family members, friends, lovers, gallerists, collectors of all stripes, museum directors, auction house staff, academics, and artists—I have pieced together how Basquiat and his work achieved the level of recognition they enjoy today.

Since the publication of what was long considered the definitive biography of Basquiat over twenty-five years ago, much has changed with respect to his reputation and in the market for his work. In writing this book, I have drawn not only on the stories shared by those I interviewed, but also on newly available or previously difficult-to- access information about Basquiat’s early life and brief career (including numerous photographs of him, some that have never been published before). These resources have helped uncover fresh insights into his life and art while correcting elements of what has become the accepted narrative. Unraveling the myth to connect with the gifted child, teen-ager, and young artist (who would have turned sixty-five this year) is the focus of the first part of this book.

Basquiat’s personal biography ended tragically in 1988, and until now, that was largely where the story stopped. Therefore my other goal here is to present the biography of his work’s survival and how, in the decades since his untimely death, both the artist and his work have attained an almost mythical status. The legacy of any great artist extends beyond their lifetime, often shaped by a small group of individuals who, motivated by varied interests, ensure the work continues to be seen, known, and experienced. For Basquiat, this was particularly true, given the significant obstacles his work had to overcome to secure the recognition it enjoys today. Additionally, his posthumous reputation was further strengthened by a shift among curators and academics toward examining art through the prism of identity—exploring how an artist’s race, gender, and sexuality inform their engagement with themes such as oppression, discrimination, and inequality. Basquiat not only embodied this evolving paradigm of artistic relevance but also helped to define it. How these and other forces combined to elevate Basquiat’s legacy—until now, the missing chapters of his story—are the focus of the second half of this book.

During his brief but prolific career, Basquiat produced approximately one thousand paintings and two thousand drawings. Many of his most celebrated works are readily accessible online through articles, websites, and Instagram posts. The Basquiat Estate has further capitalized on his legacy by licensing images for a wide array of consumer products, from shoes and underwear to candles and cosmetics. Yet this wave of commercialization masks a more complex and previously untold story—one tied to his highly accomplished but conservative accounting executive father, Gerard—which explains why this book does not include reproductions of Basquiat’s art. Over decades, his father vigorously promoted his son’s work while carefully curating Jean-Michel’s narrative, suppressing elements he found uncomfortable or unacceptable: his traumatic childhood, his bisexuality, and the impact of his addictions on his art. These efforts profoundly influenced Basquiat’s portrayal in exhibition catalogs and museum retrospectives over the past three decades. Ironically, for an artist whose work is so deeply entwined with personal identity, much of the scholarship has glossed over the very experiences that inspired many of his most celebrated creations.

The art world, like many creative industries, selects and elevates its luminaries in ways that can appear enigmatic, inscrutable, or even arbitrary. Yet its influence on our cultural landscape is profound. It is my hope that the stories I share about Jean-Michel Basquiat’s against-all-odds journey from his Brooklyn childhood to the pinnacle of the art world, will help readers understand the surprising and often hidden reasons why his paintings, rather than another artist’s, are on T-shirts worn by people around the world, on the walls of billionaires, and remain such a source of inspiration to creatives globally.

Buying Basquiat

Long before Andy Warhol, known for championing Jean-Michel Basquiat, there was Stéphane Janssen—a Belgian art collector in Beverly Hills who recognized the young artist’s genius early on

Jean-Michel Basquiat in 1981, aged 21. ©Edo Bertoglio, New York, 1981

*This article first appeared in the November 13, 2025 edition of Air Mail

Long before Andy Warhol, known for championing Jean-Michel Basquiat, there was Stéphane Janssen—a Belgian art collector in Beverly Hills who recognized the young artist’s genius early on

Ambitious young artists know they’re only as good as their first collectors. The right ones send a powerful signal, marking an artist as worth watching and worth buying.

While writing my book Jean-Michel Basquiat: The Making of an Icon, the first major biography of the artist in nearly 30 years, I set out to track down his earliest collectors, the ones who believed in him long before Andy Warhol entered the picture. I knew a few from my time as president of the Americas for Christie’s, but the one that intrigued me most was Stéphane Janssen. His name surfaced repeatedly in catalogues as the owner of key early works, yet he had vanished from view, leaving no digital trace. During the coronavirus lockdown in July 2020, I found one of his sons, who connected me to Janssen himself, then 84 and eager to share how he came to collect Basquiat and know the artist personally.

Stéphane Janssen, the great-great-grandson of Ernest Solvay, a Belgian entrepreneur whose namesake chemical company laid the foundation for dynastic family wealth, grew up in a small town near Brussels. After a brief stint in the family business, he broke away in 1965 to open a Brussels gallery devoted to the avant-garde CoBrA movement. The European group’s work was raw, colorful, and untamed, inspired by children’s art and Norse mythology. The name CoBrA came from the initials of the cities where its founding members lived: Copenhagen, Brussels, and Amsterdam.

After 11 years in the art trade, Janssen closed his gallery, saying he was weary of what he described as a life of lies and deceptions. He left his wife and children in Belgium and moved to Los Angeles to live openly as a gay man. In 1981, he met the love of his life, a waiter at a popular Los Angeles restaurant, and the two settled in a spacious Beverly Hills home, which offered ample wall space for both his Belgian collection and the new works the couple avidly acquired.

In early 1982, Janssen read a Los Angeles Times review of a 21-year-old artist’s first show in the city. Intrigued, Janssen visited the newly opened Larry Gagosian Gallery and instantly fell in love with the work. That day, he purchased a life-size painting of a Black man standing beside the scales of justice for $8,500. Janssen saw echoes of great 20th-century masters in Basquiat’s work, but also something wholly fresh and innovative. It was the first of 13 Basquiat paintings the collector would acquire by the end of 1985—works that today would be worth more than $200 million. “It was exactly the kind of work that I love, which tends to be brutally tough work,” Janssen recalled. “After seeing my collection, a psychologist once told me that I must be a very peaceful man because only murderers buy Renoir and flower paintings.”

After acquiring his first painting and learning that Basquiat was in Los Angeles, Janssen invited the artist and Larry Gagosian to his Beverly Hills home for lunch. As he walked Basquiat through his collection, which included major works by Jean Dubuffet, Pierre Alechinsky, and Karel Appel, Basquiat repeatedly muttered, “That’s shit … That’s shit too … So is that.” The only items that garnered his admiration were drawings by Hergé, the Belgian cartoonist best known for a series of books titled The Adventures of Tintin. Basquiat was delighted to see them, telling his host that he had read all the books during his elementary-school days in Brooklyn. Janssen quickly realized that Basquiat was intent on shocking him. “He was smoking a joint the size of an ice-cream cone when he arrived,” Janssen remembered. “I’d never seen anything like it. I didn’t use drugs, nor did I like being around people who were using them.” But Basquiat’s indiscretions had no impact on him. As a former contemporary-art dealer, he was well accustomed to the provocations of artists.

Later that year, while Janssen and his partner were in New York, Larry Gagosian brought them to Basquiat’s Crosby Street studio. The artist showed up an hour late, mumbling that he had been at the Metropolitan Museum admiring a13th-century crucifix by Cimabue. The work, badly damaged in the 1966 flood in Florence, Italy, had recently been restored and was on temporary loan at the Met. “We spent two or three hours together talking about different things, including the Cimabue painting, which I’d also seen,” Janssen recalled. “We had an extraordinary conversation, because he wasn’t high. He was sober and brilliantly intelligent. He was very taken with Cimabue’s depiction of the dying Christ and explained that he did something similar when he painted a Black man on a refrigerator door.”

During that visit, Janssen purchased Versus Medici, a large painting of a single, warrior-like figure, for $8,000. Many years later, in 2017, the collector who acquired it from Janssen sold the work at Sotheby’s for $50.8 million.

Janssen met Basquiat several more times, but the artist was always high. “I only saw him smoke pot. I never saw him use coke or heroin. He was not someone I liked when he was high, because he didn’t want to talk about anything except money. He would never talk about his art or what others were making.” Still, the Crosby Street visit stayed with Janssen: “I had a revelation about how intelligent he was and how educated he was about the history of painting. I discovered then that he was as great as his paintings.” (On August 12, 1988, the 27-year-old artist died of a heroin overdose in his New York City loft after a night of partying.)

For two months, Janssen was remarkably generous with his time, joining Zoom calls, sending me his Basquiat files with purchase invoices, and e-mailing new recollections as they surfaced. On our final call, he told me it would be the last. Only then did he share that he had been diagnosed with terminal cancer. He said how much he had enjoyed reminiscing about Basquiat and thanked me for bringing moments of joy back into his life. He died a few weeks later, on September 17, 2020.

Doug Woodham is managing partner of Art Fiduciary Advisors and the former president of the Americas for Christie’s

Photo: © Edo Bertoglio

What To Do With a $45 Million Art Collection?

A nagging concern for many collectors is what to do with a collection passionately assembled over time, if or when their circumstances change. It’s a complicated question without a one-size-fits-all answer. One of my clients gave me permission to share (on a disguised basis) the integrated plan we created last year for their collection. It serves as an example of what’s involved in creating a pragmatic financial plan for a valuable art collection.

Art collecting is a passion sport pursued by many, and at many different price points. A nagging concern for some collectors is what to do with a collection ardently assembled over time, if or when their circumstances change. It’s a complicated question without a one-size-fits-all answer. The right approach will depend on family dynamics, tax and financial planning considerations, and the value and composition of the collection.

One of my clients gave me permission to share (on a disguised basis) the integrated plan we created last year for their collection. It serves as an example of what’s involved in creating a pragmatic financial plan for a valuable art collection.

SETTING THE STAGE

Let’s start with some context. “Sally” and “John” started collecting in the early 1980s, when John began to make serious money. They felt post-war and contemporary art was more accessible than European modernists or Old Masters, and so focused their collecting efforts there. They supported their local museum and traveled regularly to NY and other cities to visit galleries and museums. They developed relationships with a few trusted curators and turned to them for input and advice. After years of engagement, they stopped collecting about 10 years ago.

Now in their late 70s, Sally and John enjoy living with their collection, which is spread across three homes. They have 3 adult children, all of whom are financially independent. In addition to their real estate assets and art collection, they have a substantial investment portfolio.

While working with their trusts and estates lawyer and financial advisor to update their wills, they decided they needed to better incorporate their art collection into their legacy plan. That’s when I got involved to help them think through their options. The objective was to help them achieve peace of mind, knowing their collection was thoughtfully positioned for the future.

UNDERSTANDING THE COLLECTION

The first step in the process was to assess the value of the collection and any issues associated with the physical objects. John and Sally weren’t sure what their collection was worth after ten years of not following the market actively. But it was relatively easy to “mark-to-market” the collection for financial planning purposes, because most of the artists in it were well known and regularly traded at auction.

The ninety objects in the collection were worth around $45 million. As is true for most collections, value was highly concentrated -- just fifteen artworks represented about eighty-five percent of the total value of the collection. The couple also had substantial long-term capital gains embedded in the collection: they spent about $4 million to acquire the works in the collection.

During this phase of the project, I noticed that two works had condition issues, which is not uncommon. One object was a $4 million painting that hung in their dining room. Like many collectors who get used to living with their art, they hadn’t noticed a food stain on the bottom of it. Luckily, we were able to find a conservator who specialized in work by that artist, who restored it back to its original condition.

Sally and John also owned a photograph by a living artist which had been damaged from excessive light exposure. It hung in a hallway with skylights. Without the light damage, the photograph would be worth around $400,000. But given its diminished state, it was now essentially worthless. I was able to negotiate a financial deal with the gallery that represented the artist to get the photograph reprinted. The artist supervised the process and signed the new work for a fee equal to approximately 10 percent of the fair-market-value of the work.

During this phase of the project, I also identified necessary changes to make in their art insurance policy, and put the updated policy out to bid via a broker specializing in fine art.

GOAL SETTING

Once that work was done, we held several working sessions to discuss potential goals for their collection. Three factors helped set a direction.

First, none of their children lived lifestyles consistent with owning and displaying valuable art in their homes. All of them were also slated to receive substantial inheritances. Second, if Sally and John gave the collection to their local museum, the museum would likely keep it in the basement, but for a small group of objects. Lastly, the couple had enough liquid assets (i.e., stocks and bonds) so that the executor of their estate would not have to sell the art quickly to pay estate taxes.

DISPOSITION PLAN

Armed with this information, we divided the collection into three parts.

The first was called the “core collection” because it was comprised of twenty-five objects worth approximately $35 million. All these objects would be held long-term and sold after the death of the surviving spouse. Sale proceeds were designated to go to charities important to the collectors.

Next, two valuable painting were set aside to create a gifting currency. More specifically, the paintings were transferred into a single purpose limited liability company (LLC). Sally and John would annually gift shares in this LLC to their three children and seven grandkids. Across the ten recipients, they would be able to remove $300,000 of value out of their estate each year. The two paintings we picked were easy to value, so the annual process for revaluing LLC shares would be very straightforward.

Lastly, the remaining objects in the collection were assigned to the “for sale” collection. This represented most of the objects in the collection. We added a few valuable objects into the mix to make the “for sale” portfolio more interesting to auction houses. This would enable us to negotiate a better financial deal when sold. This sale would also be timed to allow my client to realize some losses in their venture capital portfolio. By doing so, they would be able to net capital gains on the collection sale with capital losses in their venture capital portfolio, lowering the capital gains taxes they would otherwise pay on the sale of the art.

A few other noteworthy flourishes were embedded in the plan. When the core collection is ultimately sold after both Sally and John have passed, sale proceeds will be distributed in an interesting way. Thirty percent is slated to be donated to their local museum. It’s their way of giving back to an institution they love. The museum is thrilled with the prospect of getting cash rather than art. The remaining seventy percent of sale proceeds will be put into a donor advised fund. Their three adult children will then be tasked with distributing this money over ten years to a shortlist of non-arts related charities.

Sally and John are also downsizing. They will keep their New York City pied-à-terre but are selling their other homes and plan to make Florida their primary residence. When this happens, two valuable paintings in the New York apartment will move to Florida so their value will not be subject to New York State estate taxes. But rather than looking at blank walls in the future, replicas are being created so the wonderful ambiance of the NYC apartment is maintained. Technology now makes it possible to create replicas that the naked eye can’t distinguish from the original.

The Florida home will also be outfitted with state-of-the-art sensors so that light levels, humidity, and temperature can be monitored remotely from their iPhones. I also worked with the couple to rent short-term storage space they can elect to utilize on a moment’s notice so that when dangerous storms approach the Florida coast, they can be assured of being able to move artworks into a space on a high floor of a secure art storage facility.

Sally and John now have a plan for their collection that is specifically tailored to their personal goals for legacy and philanthropy. As you might imagine, cookie-cutter solutions don’t exist. But I hope this case brings alive what collectors can do to ensure that a collection passionately assembled over time is thoughtfully positioned for the future.

THREE FACTORS

Stepping back from the specific case of Sally and John, I believe collectors can assess whether they need a holistic financial plan for their collection based on three factors.

The first factor is the percent of family wealth tied up in art. The higher that percentage, the more important it becomes to have an art-related financial plan.

Second, given the fundamental illiquidity of art, how liquid is the collector’s remaining balance sheet? If it’s similarly illiquid, perhaps because it’s invested in real estate and private equity, it becomes more important to have a plan for the art collection.

Lastly, how many objects are in the collection, and in how many different collecting categories? The larger and more diverse a collection, the more important it is to have a financial plan that reflects the idiosyncratic and nuanced marketplaces where objects in each collecting category are traded.

If you have any questions about the topics covered in this article or how they may apply to your personal situation, please contact me at dwoodham@artfiduciaryadvisors.com.

--------------------------------------

Doug Woodham is the Managing Partner of Art Fiduciary Advisors, a NY-based firm which provides art-related financial consulting to collectors and institutions. He most recently served as President of the Americas for Christie’s. Earlier in his career, Doug was a partner with McKinsey & Company, working with asset and wealth management clients in the U.S., Europe, and Asia. Doug is also the author of Art Collecting Today: Market Insights for Everyone Passionate about Art (2017), which received excellent reviews in a variety of outlets, including the New York Times, the Economist, and the Financial Times.

A version of this article appeared in Wealth Management Magazine and Artsy Magazine in June 2020.

Artwork: David Hockney, American Collectors (Fred and Marcia Weisman), painted in 1968. Currently in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Gallery or Auction House? When to Buy from Each

With so many works for sale, a recurring question for collectors is whether galleries or auction houses offer buyers a better deal. Based on my experiences as a collector, art advisor, and former President of the Americas for Christie’s, the answer depends on context and the type of work being sold.

Compared with the beach a few blocks away, Miami’s convention center may not look like much. But for a week each December, the convention center, home to Art Basel in Miami Beach, becomes a paradise for collectors. The hallways and gallery booths hold wonderful surprises. The 82,000 visitors attending this past December could see close to 10,000 works of art worth an estimated $3.5 billion. Just one month before, the auction houses Sotheby’s, Christie’s, and Phillips had offered work by many of the same artists. Those November auctions, which feature the most expensive art available, included close to 1,900 works which sold for a combined $2.3 billion.

With so many works for sale by the same artists, a recurring question for collectors is whether galleries or auction houses offer buyers a better deal. Based on my experiences as a collector, art advisor, and former President of the Americas for Christie’s, the answer depends on context and the type of work being sold. But there are some general principles that explain the relationship between the price of artworks at galleries and those fetched at auction (including the buyer’s premium).

IF AN ARTIST TRADES INFREQUENTLY AT AUCTION, THEN THAT ARTIST'S AUCTION PRICES ARE LIKELY TO BE LOWER THAN GALLERY PRICES

Galleries spend considerable time and money building and cultivating a buyer base for their artists. Because artists create unique objects, and collectors’ appetites for the same artist can vary widely, finding a buyer for each work takes time. Ask three people at a gallery opening to point out their favorite work, and you will likely get three different answers. Because most artists have a small buyer base, it is hard to know if a buyer who is both aware of the artist and interested in the specific work for sale will emerge on the day of an auction. If the work sells, then it will most likely go for less than what the gallery would ask for similar work. As a rule of thumb, artists whose work appears at auction no more than three times a year will likely cost less at auction than equivalent work at a gallery.

GALLERIES RATIONING WORK BY "HOT ARTISTS" TEND TO PRICE IT TOO LOW, LEADING TO PRICE SPIKES IN THE AUCTION MARKET

Galleries experience both pleasure and pain managing the sales of work by “hot artists.” To get works placed with the “right” collectors and institutions, galleries may offer discounts relative to what other “less desirable” collectors may be willing to pay for it. The gallery may also be reluctant to jack up prices too quickly, out of concern for potential problems down the road if the artist’s career pauses. But when work by the artist leaks into the auction channel, buyers who were unable to purchase work through the gallery crowd into the auction market, driving up the price. Speculators may also jump into the game, helping push auction prices significantly above gallery prices.

Njideka Akunyili Crosby is a recent example of this phenomenon. After a Yale MFA and a 2011 stint as an artist-in-residence at the Studio Museum in Harlem, her distinctive work started to appear in group shows and a few one or two-person exhibitions at galleries focused on emerging artists. Her break-out year from an institutional perspective came in 2015 when the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles and the New Museum in New York featured her work in its Triennial. The commercial art world was not far behind when the Victoria Miro Gallery in London announced they would represent her. Crosby’s highly anticipated first show opened on October 4, 2016. In an interview with The Economist magazine, the gallery said that more than a dozen public institutions were vying to buy her work and that the gallery was offering them paintings for less than $100,000. Given institutional demand and their preference to see the work in public collections, the gallery said it did not anticipate selling any works from the show to private collectors.

While artists and galleries aspire to control prices, much is beyond their control. In Crosby’s case, it was the lucky private collectors who already owned her work who profited most. Shortly after the Victoria Miro show closed, Sotheby’s included a painting by the artist in its November 17, 2016 Post-War and Contemporary Art evening sale. With a pre-sale estimate of $200,000 to $300,000, it sold for $1.1 million (including buyer’s premium). Four months later, Christie’s sold a slightly larger work in their London Post-War and Contemporary Art evening sale for $3.1 million (including buyer’s premium). By trying to keep prices low, the artist and gallery effectively enabled early collectors to enjoy windfall gains, rather than themselves. The takeaway: Buying a hot artist at auction is unlikely to be a deal, but may be the only option under these circumstances.

WHEN AN ARTIST'S CAREER IS IN A SLUMP, GALLERY PRICES ARE LIKELY TO BE SIGNIFICANTLY HIGHER THAN AUCTION PRICES

As an artist’s career develops, galleries raise prices to reflect not only higher demand but also to signal to buyers that the artist is on an upswing. They do this because many buyers find it hard to evaluate an artist’s importance and sometimes use price increases as confirmation the artist is doing well. But if demand slumps for an artist’s work, galleries hate lowering prices, fearing that doing so will publicize to collectors that the artist’s career has paused, or worse. But when work by the artist comes up at auction, it sells for its fair market value, which is far below the artificially high price galleries continue to ask for it.

To protect the innocent, I will avoid naming artists who are in this predicament. But it is easy to figure out by comparing offering prices at galleries with readily available auction pricing data. The good news for collectors is that if you love an artist in this situation, you should consider buying their work at auction. Many collectors use alert systems offered by Artsy, Artnet, and other providers, to let them know when a work by an artist they are interested in is coming up for sale at auction.

MASTERPIECE COLLECTORS ARE OFTEN WILLING TO PAY MORE FOR SOMETHING AT AUCTION THAN PRIVATELY

Masterpiece collectors know that there is only a very small pool of potential buyers with the means and desire to spend tens of millions on a work of art. As a result, it is difficult for them to know with confidence the fair market value of an object. A recent example was a beautiful Constantin Brancusi bronze head of a sleeping woman, La muse endormie (1909-1913), offered at Christie’s in May 2017 with a pre-sale estimate of $25 to $35 million. Nothing like it had been on the market for years. What was it worth? If offered privately, even high-rolling collectors might balk at paying a big price for it, because the price had not been publicly validated. This resistance can drop away during an auction when they see other bidders going after it. Auction house specialists are full of stories of fruitlessly trying to sell a masterwork privately for a big number, only to see the same clients bid against each other when the work goes on the auction block. They often end up paying more than the price initially offered to them. That Brancusi? It ended up selling for $57.3 million.

ONLY IN VERY LIQUID MARKETS ARE AUCTION AND GALLERY PRICES LARGELY THE SAME, BUT EVEN THEN, SHORT-TERM DIFFERENCES CAN REWARD THE DILIGENT BUYER

A liquid market creates visibility around the fair market value of an artist’s work, making it hard for pricing differentials to persist between the two sales channels. The Yayoi Kusama market, for example, tends to be quite liquid because she has been so prolific. Buyers do not have to search high and low to find something to buy. If they’re unable to get something from one of the galleries that represent her, they can buy something at auction, or at an upcoming art fair, or call around to the numerous galleries that offer her work on the secondary market. Comparison shopping by diligent buyers forces similar work to sell for similar prices. But even in the Kusama market, there are periods where sale prices at auction are higher, only for the relationship to flip. This happens because the number of Kusama “shoppers” at a given point in time is small. So if they act more on impulse, with little or no comparison shopping, they risk overpaying in one channel.

Capturing the deal opportunities discussed above requires research and discipline. But research and discipline can transform a casual buyer into a smart collector. Start with a short list of artists you would ideally like to acquire. Monitor whether their work comes up at auction. When it does, talk with auction house specialists to get their perspective on the work and how they arrived at their presale estimates. These are very easy conversations to have because specialists love speaking with potential buyers. Stay abreast of news about your shortlisted artists so you can sense whether changes may be afoot in their career trajectories. Key indicators to follow include changes in gallery representation, the frequency with which the artist is included in group shows, whether museums are supporting the artist via exhibitions and acquisitions, and the breadth and depth of press coverage. Lastly, when work by your short-listed artists appear in gallery shows or at art fairs, always ask about pricing. Even if the work has already sold, gallery staff will often be willing to share intelligence on sale prices. By following these practices and disciplines, buyers increase greatly the odds of getting a good deal.

*This article appeared in Artsy Magazine on March 20, 2018. Click here.

Doug Woodham is the Managing Partner of Art Fiduciary Advisors, a NY-based firm focused on providing art-related financial advice to collectors and institutions. Earlier in his career, Doug was President of Christie’s for the Americas and a Partner with McKinsey & Company. He is also the author of the best-selling book Art Collecting Today: Market Insights for Everyone Passionate About Art (2017).

Tips for Negotiating Art Museum Gift Agreements

Art museums in the United States live on the generosity of individuals. Most of the financial support they count on for their annual operating budgets come from individuals, or foundations and trusts set up by them.

Art museums in the United States live on the generosity of individuals. Most of the financial support they count on for their annual operating budgets come from individuals, or foundations and trusts set up by them. Moreover, because art museums rarely have substantial acquisition-related endowments, they depend on bequests and donations to grow their collections. The Association of Art Museum Directors, for example, reported that 80 percent of the objects entering North American art museums in 2016 came from donations or bequests.

If you are considering making a major gift to an art museum, then it is important to understand how museum development staff can collaborate with you to design a mutually beneficial gift agreement. The first important question is whether you want to donate cash, art, or some combination of the two. If just cash (and/or marketable securities), then the negotiation process will revolve principally around five variables: restrictions on use, contribution timing, matching requirements, donor recognition, and reporting requirements on use of funds. While there is some subtlety and nuance associated with negotiating these types of agreements, donating art is generally much more complicated because the needs and interests of the museum and collector are more likely to diverge.

Collectors and museums both love art and objects, but they may have different views on which works are important to scholars and museum audiences. Moreover, because most museums can only show a fraction of their collection at any one time (generally 5 percent or less of the total object count), they are loath to enlarge their collections with material that will spend most of its time in costly storage facilities. One of the biggest planning mistakes collectors make is to assume that art museums will be excited to accept works from their collection.

Collectors should start the donation process by creating a short list of museums where they would like to see the work(s) go. The more important the museum, the more important the work needs to be. To avoid disappointment, it is best to have different levels of museums on the list. If you know with certainty that you will donate the work after finding a suitable home for it, then there is less of a need to get an appraisal before contacting museums. But if the value of the object will influence whether or how you donate it, then first get an appraisal from a qualified professional. This is especially true for works with a potential donation value of $50,000 or more because the appraisal will be closely scrutinized by the IRS.

Assuming a suitable museum is interested in the work(s), there are three basic donation deal structures: donate the work now; make a promised bequest; or donate a fractional interest, perhaps 25 percent, with the balance donated later. There is one additional deal structure, called a bargain sale, but it is rarely used. This occurs when the museum is offered the opportunity to buy the work for less than its fair market value. The collector gets a charitable donation equal to the difference between fair market value and the sale price, along with sale proceeds. These deal structures have very different financial planning, tax, and operational implications. As a result, collectors need to be acutely aware of the differences so they can make an informed decision on whether and how to proceed.

CASE STUDY: DONATING A MAJOR COLLECTION

Sally and John, collectors who want to remain anonymous, have a wonderful collection of drawings, paintings, and sculptures by leading American and European Post War and Contemporary artists. Because their children will inherit a great deal of wealth, and none are interested in living with the collection, the couple decided to pursue donating their collection to a major institution. After selecting three museums, they negotiated simultaneously with all of them to get the best possible promised gift deal. Because of the quality of the collection and their willingness to work creatively with the institution around deal structure, they inked an agreement with the following terms:

Timing. Title to the collection will go to the museum after both Sally and John have passed away. Until then, the collection will remain in their homes for them to enjoy.

Museum obligations. The museum will publish an illustrated catalog on the collection, including essays by leading scholars, within 4 years of signing the promised gift agreement. The museum will also mount a show of important work from the collection, coupled with an education and outreach program evangelizing the significance of the gift to the museum, to coincide with the publication of the catalog.

Optionality. Due to the size of the collection and the long-term costs the museum will incur for preservation, restoration, storage, and display, Sally and John gave the museum the right to sell non-core elements, subject to certain timing restrictions. In return, the museum committed to keep core elements of the collection [which was a defined term in the promised gift agreement] in perpetuity and to show these works at least once every 5 years, either individually or in groups.

Annual contributions. The couple agreed to make substantial unrestricted annual contributions in each of the next 5 years to support museum programming, acquisitions, and research.

Donor recognition. While the museum wanted to announce the promised gift when the agreement was signed, the couple instead elected for the announcement to occur when the collection show opens at the museum. They also elected to have their annual unrestricted contributions be noted in all museum publications as ‘anonymous’ so as to minimize unsolicited requests for funding from other philanthropic organizations.

A version of this article appeared in Negotiating Charitable Gifts, a special white paper published by UBS in November 2017 for their private banking clients. Click here for a PDF copy of the paper.

Doug Woodham is the Managing Partner of Art Fiduciary Advisors, an advisory practice based in New York City that helps clients create legacy plans for their art collections. The firm offers comprehensive services, from clarifying family goals and evaluating alternative disposition strategies, through the execution of donation and sale agreements. The firm also advises collectors, artists, and institutions on the sale of art so they can be assured of maximizing sale proceeds in a very complex and opaque art marketplace. Earlier in his career, Doug was President of Christie’s for the Americas and a Partner with McKinsey & Company. He is also the author of the best-selling book Art Collecting Today: Market Insights for Everyone Passionate About Art (2017).

“Collectors and museums may have different views on which works are important to scholars and museum audiences”

Identifying and Managing Conflicts of Interest in the Art World

One accurate cliché of the art world is that nothing matters more than relationships and information. High-end art dealers and auction houses know this better than anyone. How do they acquire these relationships and information?

One accurate cliché of the art world is that nothing matters more than relationships and information. High-end art dealers and auction houses know this better than anyone. How do they acquire these relationships and information? In addition to the old-fashioned ways of meeting new prospects (at art fairs, say, or by hosting elaborate dinners and events), some use the services of paid go-betweens.

These go-betweens -- art advisors, curators, even family members -- can net tens to hundreds of thousands of dollars in fees on a single transaction, paid out as “introductory commissions,” or ICs. Surprisingly, their roles are sometimes hidden.

One collector I know bought a valuable painting from a gallery in the late 1990s, based in part on a glowing recommendation from a museum curator. Years later, when the collection was appraised, the collector was shocked to learn it was a fake. The gallery initially refused to refund the money, only acquiescing when it became clear the collector was willing to fight. To add insult to injury, unbeknownst to the collector, the gallery had paid the museum curator a sizeable introductory commission on the sale, and would only reimburse the collector for the sale price minus the IC payment. The collector now had an additional fight on their hands to get all their money back.

That’s just one of many cautionary tales. They illustrate why collectors active at the high end of the art market need to take steps to protect themselves, both as buyers and sellers.

SELL-SIDE INTRODUCTORY COMMISSIONS

To win consignments, auction houses sometimes pay introductory commissions to individuals who can influence which house the consignor selects to handle the sale. For example, suppose a collector is thinking about selling part of their collection. Having not sold many works before, she is uncertain about how to proceed. If someone close to her offers to introduce her to the right auction house to handle the sale, the seller is likely to take them up on the friendly offer. The introduction takes place, and sometime later the collector signs a consignment agreement with that auction house.

However, that person may have been sharing information with the auction house without the collector’s knowledge. Such information could inform how the auction house approaches and negotiates with the collector-- e.g., what is motivating them to sell, whether they are savvy deal negotiators, or what type of specialist team will impress them. The go-between may also have an agreement with the auction house to be paid a success fee, perhaps two percent of the final hammer price. The more important their contribution to the auction house in winning the consignment, the higher the IC they may receive. From the perspective of the auction house, the IC is yet another cost to be netted against the buyer’s premium they earn on the sale.

Sometimes the payments are for legitimate services the consignor is aware of. But each auction house has its own policy on who is responsible for disclosing to the consignor that ICs related to the sale of their property are being paid. Some stipulate that the IC recipient is solely responsible for disclosing this fee, absolving the auction house of any responsibility. Others may include a reference to a third-party payment in the consignment agreement, without mentioning its size or value. As a result, consignors may not be aware of the existence or magnitude of introductory commission payments, nor that information they may have presumed was confidential was being shared with an auction house. In these types of situations, the consignor is effectively paying the third party for services they may never have agreed to pay for, had they been informed Moreover, the IC payment warps the economics of the deal, because the collector and auction house could have elected to share the go-between’s fee in some other way.

Given these limited disclosure practices, what should collectors do to protect themselves? First, tell the auction house that any third-party fee arrangements related to the sale of their property must be fully disclosed. Since an auction house is an agent for the seller with an implied fiduciary duty, there should be no pushback on this request. If there is, the collector should immediately stop discussions. Second, this disclosure should be incorporated into the formal consignment agreement. The auction house should provide representations and warranties that it has informed the consignor of all the names and payments that will be made to third-parties related to the sale of their property.

BUY-SIDE INTRODUCTORY COMMISSIONS

To attract buyers, galleries sometimes feel obligated to pay introductory commissions to art advisors or other third parties. But undisclosed introductory commissions taint the advice a collector receives. For example, let’s say an art advisor has an agreement with a client that allows her to bill a 10 percent fee on top of the sale price of any work the client buys based on her recommendations. The advisor may also have a side arrangement with a gallery in which she also gets a 10 percent IC from the gallery on all sales made to clients of the advisor. The payment from the gallery no doubt influences what the art advisor recommends to her clients. But it is up to the gallery and the advisor to decide whether to inform the client of this payment.

Undisclosed ICs have an additional complication - the buyer will likely overpay for the art because the IC negatively impacts the gallery’s willingness to negotiate on price. For example, suppose a gallery has a typical deal with an artist in which sale proceeds are split 50/50. To sell the work, the gallery may be willing to extend a 15 percent discount to the buyer, which comes out of their share. The gallery will keep 35 percent of the offering price to cover staff costs, rent, and other overhead. But if the gallery must also pay an art advisor a 10 percent IC, it again impacts the economics of the sale. The gallery will be far less willing to offer the same 15 percent discount, which drives up the price for the buyer.

Buyers should consider adding language to a purchase agreement along the lines of “no payments have been or will be made to any third party related to the purchase of the artwork without my prior knowledge and consent.” Most galleries will be willing to include language like this in purchase agreements, but it is best to mention it up front, so the buyer can get the best deal terms possible. If the collector uses an art advisor, they should also include language in the advisor agreement like “the advisor will not accept any fee from a gallery or other third party, in cash or in kind, related to works of art that I purchase based on their advice.”

* * *

Collectors are harmed when introductory commissions are not fully disclosed. On the buy side, they risk being seduced into buying things they shouldn’t, or paying too much for an art work. On the sell side, they risk receiving less for their property because a portion of sale proceeds is siphoned off to an undisclosed third-party. But sunshine is the best disinfectant. Collectors can protect themselves by asking questions, and including in their purchase and sale agreements the disclosure language mentioned above.

A version of this article appeared in Artsy Magazine in January 2018.

Doug Woodham is the Managing Partner of Art Fiduciary Advisors, a NY-based firm focused on providing art-related financial advice to collectors and institutions. Earlier in his career, Doug was President of Christie’s for the Americas and a Partner with McKinsey & Company. He is also the author of the best-selling book Art Collecting Today: Market Insights for Everyone Passionate About Art (2017).

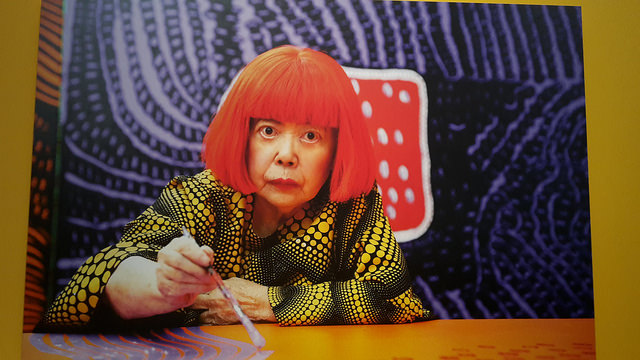

The Reigning Queen of the Art Market

When Yayoi Kusama moved to the United States in 1957 at the age of twenty-eight, she was an ambitious young artist tired of the conservatism and discrimination she faced in her native Japan.

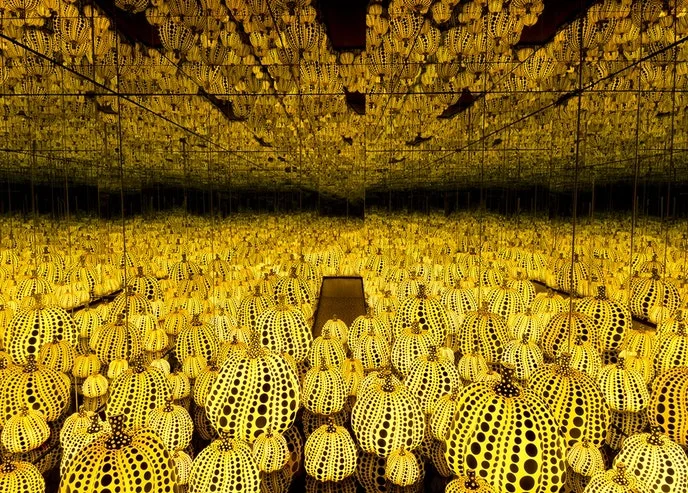

When Yayoi Kusama moved to the United States in 1957, age 28, she was an ambitious young artist weary of the conservatism and discrimination she faced in her native Japan. She settled in New York, quickly becoming part of the avant-garde art scene, where she developed her several signature motifs. She loved brightly colored polka dots, sometimes covering an entire painting, wall, or room with them so that the polka dots obliterated the underlying support. She created mirrored rooms with suspended colored lights which made visitors feel they were part of an ethereal infinity. She also created large, monochromatic paintings called infinity net paintings filled from edge to edge with painted loops. The simple act of painting loop after loop created surprisingly complex paintings that seemed to have different points of tension as viewers scanned their surfaces.

These works, which she has consistently produced over more than five decades, were not always a commercial success. Today, she is one of the few women who consistently rank among the highest-selling living artists by sales volume and value. What accounts for her present popularity, and what does it tell us about the art market? Her partnership with consumerism is an important factor behind her career renaissance, but her work is also uniquely suited for our Instagram age. Her journey runs from downtown New York to Japanese mental hospital to the windows of Louis Vuitton boutiques and beyond.

THE FAME-HUNGRY, ANTI-WAR NEW YORK WORKAHOLIC

In 1959, Kusama showed five large infinity net paintings in her first New York exhibition. Each was composed of thousands of individual white loops painted on a black ground. Donald Judd, who at the time worked as an art critic for ARTnews, wrote in his review that “Yayoi Kusama is an original painter. The five white, very large paintings in this show are strong, advanced in concept and realized.” He went on to say “The expression [in the paintings] transcends the question of whether it is Oriental or American. Although it is something of both, certainly of such Americans as Rothko, Still and Newman, it is not at all a synthesis and is thoroughly independent.” It was high praise from a curmudgeon.

Kusama was a workaholic. Moreover, she was obsessed with being noticed and recognized; she hungered to be famous. She found her way to the center of the action, be it people, parties, or performances. Because she created provocative work for the time, it was easier for her to be noticed. She covered tables, chairs, and shoes with phallus objects she made of silver-painted stuffed canvas. She also organized naked anti-war happenings, including one on the Brooklyn Bridge, where participants stripped down and Kusama painted them with polka dots.

SURVIVING AND WORKING THROUGH MENTAL ILLNESS IN JAPAN

After fifteen years in the United States, Kusama moved back to Japan in 1973. She had a history of recurring psychiatric problems. When her issues became particularly acute in 1977, she elected to admit herself to the Seiwa Hospital for the Mentally Ill in Tokyo. She continued as an active artist, going to a nearby studio to work and returning to the institution for meals and treatments. But the art world is a tough place: out of sight, out of mind. She fell off the radar, reduced to an interesting footnote in the history of the 1950s and 1960s New York art scene.

She gained noticed again in the early 1990s, when she represented Japan at the 1993 Venice Biennale. Her work slowly appeared once more in gallery shows in New York, London, and Los Angeles. By the middle of the last decade, her career had accelerated, with important galleries in Europe and the United States representing her. Her rise coincided with a surge in Asian wealth and collectors there wanting to own her work. Important museum shows followed, including a major retrospective in 2011 and 2012 that traveled to the Whitney Museum in New York, the Tate Modern in London, the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, and the Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid.

PERSONAL NARRATIVE, HIGH PRODUCTION, AND SOMETHING FOR EVERYONE

Personal narratives are sometimes an important factor behind collectors buying an artist’s work. This is especially true for Kusama. I remember one conversation with a young collector couple about the artist. I asked them, “Why Kusama?”

Without hesitation, they said something along the lines of, “She’s badass. She does her own thing. She stayed true to herself and makes no apologies for it. She thumbed her nose at the world and waited for the world to come to her.” The visual and the emotional merged for this couple, who bought the highest-quality work they could afford at the time, a drawing from the early 1960s. Stories about Kusama’s mental health issues and her fierce determination and longevity help some collectors understand her work and explain it to their friends. She still craves attention and dresses to remain unforgettable, wearing bright red wigs, outfits covered with polka dots, and goes about in a polka-dot encrusted wheelchair.

As her popularity increased, so did her production. She started using studio assistants and repeating older themes, especially infinity nets. She created work in different sizes, colors, and media, including new infinity rooms and large pumpkin sculptures. An infinity room at the Broad Museum in Los Angeles is now a major tourist attraction and a destination of choice for selfies. Her work is perfect for Facebook and Instagram.

While conceptual and highly emotional, her work is accessible through its graphic nature and exciting beauty. Collectors across the globe have been drawn to her aesthetic, from the broad appeal of her gallery and museum shows to her installation in a Ginza Tokyo department store this year. Her partnership with consumerism is an important factor behind her career renaissance. She embraced consumer culture to expand her market: her partnership with Louis Vuitton in 2012 dramatically increased awareness of her work and her personal narrative. But her availability penetrates deeper than the market for million-dollar paintings and multi-thousand-dollar handbags. Enthusiasts at a more modest price point can own their own piece of Kusama through licensed key chains, mouse pads, paperweights, and polka dot pumpkin pillows.

The ready availability of her work at different price points helps stimulate demand - an odd case of higher supply generating higher demand. Buyers do not have to search high and low to find something to buy. If they’re unable to get something from one of the galleries that represent her, they can buy something at auction, or at an upcoming art fair, or call around to the numerous galleries that offer her work on the secondary market. Familiarity has not bred contempt, but instead greater interest and demand for her work. Collectors are now willing to pay extraordinary sums for her important early paintings which laid the groundwork for her fully-realized vision today. In November 2014, a white infinity net painting from 1960 sold for a new world record of $7.1 million; ten years ago, it would have sold for a fraction of this amount. For most artists, scarcity rules. But for Kusama, like Andy Warhol, embracing consumerism helped propel awareness and sales of her work.

A version of this article appeared in Artsy on November 20, 2017. Click here.

Doug Woodham is the Managing Partner of Art Fiduciary Advisors, a NY-based firm focused on providing art-related financial consulting to collectors and institutions. Earlier in his career, Doug was President of Christie’s for the Americas and a Partner with McKinsey & Company. He is also the author of the best-selling book Art Collecting Today: Market Insights for Everyone Passionate About Art (2017).

Why Becoming a National Treasure Can Lower an Artwork’s Value

While Andy Warhol believed that “In the future everyone will be famous for fifteen minutes,” the artist retains his fame today almost thirty years after his death. Warhol is, in fact, so relevant to contemporary culture that despite being a thoroughly American artist, laws in other countries increasingly categorize works by the artist as cultural property subject to export restrictions and limitations on sale.

Andy Warhol’s Triple Elvis and Four Marlons on display during the Christie’s Post War and Contemporary art evening sale on November 12, 2014

While Andy Warhol believed that “In the future everyone will be famous for fifteen minutes,” the artist retains his fame today almost thirty years after his death. Warhol is, in fact, so relevant to contemporary culture that despite being a thoroughly American artist, laws in other countries increasingly categorize works by the artist as cultural property subject to export restrictions and limitations on sale. Originally designed to protect antiquities and Old Masters, these rules and regulations are starting to ensnare art made in the 20th century.

Because they restrain trade, these laws lower the value of art that must remain in the local country, while providing no mechanism for the owner to be compensated for their loss. They also create incentives for owners to get their 20th century art out of the country before it becomes subject to the rules. Italy and Germany provide good examples through which to understand the perverse impact of cultural property laws on the marketplace for 20th century art.

In Italy, the land many believe invented bureaucracy, the fine art export rules do not disappoint. The first comprehensive Italian cultural heritage law was passed by the Italian parliament in 1909; it was recently updated in 2017. Artwork that is at least 70 years old and created by a deceased artist requires an export license to leave the country. As of 2019, this will apply to art made on or before 1949, and to all deceased artists, not just artists of Italian heritage.

The law forces Italian collectors to be on ‘death watch’ because the export status of works they own can change overnight when an artist passes away. Moreover, the rules apply to any “culturally significant” artwork worth more than €13,500. To use Miró as an example, every work created during or before 1949 that is in Italy, be it a $20,000 print or a $20 million painting, will need an export license to leave the country.

Why does this matter? Securing a license is time-consuming, plus it creates incentives for side deals and other forms of bad bureaucratic behavior. The Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities is also permitted to declare an artwork of national importance, a designation that enables them to block it from leaving the country and limit its sale to only Italian residents or institutions. Because the Ministry has no guidelines on how the concept of “national importance” should be determined, the assessment is completely at their discretion.

Elena Quarestani, an Italian collector with a Salvador Dalí painting, was entangled in these onerous rules. Milanese officials wanted to protect the Dalí portrait, Figure at a Table (1925), as an example of Italian cultural heritage, even though it is an early work by Dalí that does not incorporate any of the motifs for which he is known. But for being by Dalí, the painting would be essentially worthless. This painting only appeals to connoisseur collectors of Dalí or to an institution devoted to him, neither of which is likely to be found in Italy. But, as Quarestani told The Guardian, the government found that it was rare enough for any work by Dalí to be in Italy to warrant the export ban. The Italian government also blocked an offer by the Spanish-based Dalí Foundation to acquire the work.

By restricting the sale to Italian buyers, the government would force Quarestani to sell the painting at a discount to its true fair market value. But she has no recourse to the government to be compensated for her loss.

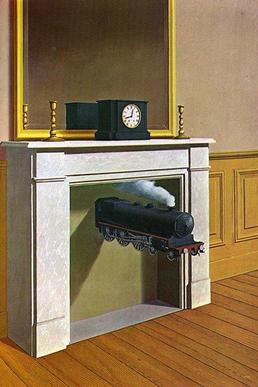

Dalí would likely be amused by the surreality of the government’s arbitrary ruling. Similarly, Warhol, who famously quipped “Making money is art and working is art and good business is the best art,” likely would have loved that two of his early paintings hung in a casino in the German town of Aachen, a spa city near the border with Belgium and the Netherlands. On their way to slot machines and poker tables, gamblers passed Triple Elvis, a 1963 silkscreen painting of three life-size images of Elvis on a a silver background, and Four Marlons, a 1966 silkscreen painting of four life-sized images of Marlon Brando on a motorcycle.

Purchased in the late 1970s for $185,000, or approximately $700,000 in current dollars, the paintings were part of a plan to glamorize an otherwise off-the-beaten track gambling parlor. When the casino conglomerate that owned the Aachen operation fell on hard times, a German state-owned bank seized control of the company and decided to sell the paintings. The sale was a reasonable action by the owners to raise cash for a troubled company. But protesters emerged, claiming this was a dangerous sale of cultural property owned by a state-run financial institution. The sale went ahead anyway, and the works sold for $151.1 million.

The sale, however, contributed to the German Culture Minister advocating for tough new rules to limit the export and sale of artwork. In July 2016, the German parliament passed legislation at the Minister’s behest. Owners of works of art worth more than €150,000 that are at least 50 years old now need an export license for the work to leave the European Union. If the work is shipped to another EU country, then the minimum thresholds are €300,000 and 75 years. Officials in each of Germany’s 16 regions were also given the authority to declare works in their region to be of national significance. They can then bar the work from leaving and restrict sale to individuals or institutions in Germany. The rules apply to art by both deceased and living artists, and artists of all nationalities. Because many German artists protested the proposed rules, the government added last-minute provisions granting living artists the right to approve whether any artworks by them are added to the export ban list. The Culture Minister indicated that if the rules were in place in 2014, she would have blocked the export of the two Warhol paintings.

As in Italy, the German law created unintended consequences as lawmakers tried to control markets. In advance of the legislation passing, many German collectors moved valuable art out of the country. With the passage of time, as more 20th century art has reached the critical export license date, more artworks have left the country. The situation has become so acute that German auction houses and galleries face difficulties sourcing consignments, and continue to agitate for repeal of the regulations.

While German collectors and art market professionals were made worse off by these rules, who benefits? Collectors in the United States and Asia probably have smiles on their faces as the art that has flowed out of Germany, and will continue to do so, becomes available for sale on the international market.

*This article appeared in Artsy Magazine on January 2, 2019. Click here to be taken to the Artsy website.

Doug Woodham is the Managing Partner of Art Fiduciary Advisors, a NY-based firm focused on providing art-related financial advice to collectors and institutions. Earlier in his career, Doug was President of Christie’s for the Americas and a Partner with McKinsey & Company. He is also the author of the best-selling book Art Collecting Today: Market Insights for Everyone Passionate About Art (2017).

Inside the Mind of David Rockefeller, Titan of Art Collecting

David Rockefeller inherited many things: a storied name, unimaginable wealth, an inquisitive mind, and a profound compulsion to collect. Both his parents had the collecting gene. His father, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., was the only son of John D. Rockefeller, the founder of Standard Oil and one of the richest individuals in American history.

David Rockefeller inherited many things: a storied name, unimaginable wealth, an inquisitive mind, and a profound compulsion to collect. Both his parents had the collecting gene. His father, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., was the only son of John D. Rockefeller, the founder of Standard Oil and one of the richest individuals in American history. John Junior collected old masters, including Duccio di Buoninsegna, Piero della Francesca, and Francisco Goya, while David’s mother, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, preferred the fresh and new. She flung herself into collecting contemporary art, which at the time meant artists such as Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, and Wassily Kandinsky. She was also a driving force in the creation of the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

David started collecting when he was a small boy. “I do not remember whether I started first with stamps or with beetles, but both collections must have been under way by the time I was ten years old,” he wrote in a special catalogue of his collection that he published in 1984. “Obviously, neither beetles nor stamps are directly cultural concerns, yet my interest in and curiosity about them set certain patterns that I suspect have influenced me throughout my years as a collector.” With his wife Peggy, David Rockefeller went on to collect masterworks across numerous categories, including 20th century European painting, American modernism, European porcelain, and English and American furniture.

A noted businessman, statesman, and philanthropist, David Rockefeller passed away in March 2017, at the age of 101. “No individual has contributed more to the commercial and civic life of New York City over a longer period of time than David Rockefeller,” said businessman and former New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg in a tribute. Shortly after his passing, the Rockefeller family announced that following David’s wishes, his collections would be sold at auction with all sale proceeds going to nonprofit organizations, including his alma mater Harvard University, the Museum of Modern Art, the Council on Foreign Relations, and Rockefeller University. Almost 1,600 lots will be offered for sale in May in a series of auctions at Christie’s. Expected to be the most valuable single owner sale in auction history, the offerings include both a Picasso painting that may go for more than $100 million and costume jewelry with pre-sale estimates under five hundred dollars.

David Rockefeller not only collected; he reflected on and wrote about his collecting, penning three essays about this lifelong passion. The first essay, written in 1984, was included in Volume One of what ultimately became a five-volume collection catalogue that Rockefeller privately published to share with friends and family. Ten years later, he wrote the foreword to a catalogue for a MOMA exhibition, Masterpieces from The David and Peggy Rockefeller Collection: Manet to Picasso. Lastly, he included a chapter on his experiences as a collector and MOMA trustee in his 2002 autobiography, Memoirs.

These reflections take us inside the mind of one of the great collectors of the 20th century. They help us understanding his thinking and what art meant to him and his family, and how it enriches us all.

STARTING TO COLLECT

David Rockefeller shared his passion for collecting with his wife Peggy, whom he married in 1940. She predeceased him in 1996.

“The first painting of any consequence we bought was a portrait of a handsome young gentleman, attributed (falsely, as it turned out) to Thomas Sully. We paid $10,000 for it in 1946, which was a great deal of money for us at the time [approximately $137,000 in current dollars]. We liked it very much, and for many years it hung over the living room mantel in New York. At about the same time, because they were reasonably priced, we bought other minor eighteenth-century English portraits, two featuring men in bright red coats and one of a girl, vaguely – and inaccurately – ascribed to Thomas Gainsborough. They at least filled blank spaces on our walls, and we found them agreeable.” [1]

“Collecting differs from mere acquisition in that it is an intensely personal experience, and Peggy and I and the other members of our family have been deeply involved in the process over the years. We have always been fascinated by the cultural history of works of art and by the circumstances under which they were created, and Peggy and I have learned widely from relatives, friends, art historians, dealers, and artists themselves, as well as from our travels and from what reading we have had time to do.” [2]

ART AND BEAUTY

Art critics and curators rarely use the word “beauty” anymore to describe a work of art, unless they want to be ironic. The notion of beauty, however, was at the core of what David and Peggy Rockefeller collected.

“The love of beauty has, of course, been the primary motivation behind our collecting. Beauty, to me, whether found in nature or in man-made objects, is ennobling and enriches the soul. It remains to me a kind of mystery, a concept somehow beyond the intellect.” [3]

“A secondary but important motivation behind our collecting is the love of diversity. We are fascinated by the wonderful interactions that can occur among pieces from different times and cultures – especially when they meet with their surroundings to create a harmonious whole. Our enjoyment of our possessions and surroundings does not necessarily relate proportionately to some artificial rating assigned by a group of experts. Rather, our enjoyment is closely associated with our recollections of how, where, and from whom we acquired our various art objects, and well as with the relationship of these objects to one another.” [4]

“We never bought a painting with a view towards “forming a collection” or to “fill out a series,” but simply because, in the end, we couldn’t resist it. Through this rather unscientific process, we have been fortunate to have surrounded ourselves with beautiful works of art that have given us unending and increasing pleasure as we have lived with them over time.” [5]

“Given other responsibilities and interests, I never have been able to devote a major portion of my time to the appreciation and collecting of art. Nevertheless, the time I have been able to find has had enormous meaning for me and contributed greatly to my own life and that of my family. Certainly Peggy and I both believe deeply that our collecting and enjoyment of man-made objects of beauty have given us a saner, more balanced, and more joyful approach to our activities in every area of life. Beauty gives one joy, and joy, in turn, generally adds new and productive facets to one’s overall perspective.” [6]

“Above all, she [Mother] taught me and my siblings to be open to all art – to allow its colors, texture, composition, and content to speak to us: to understand what the artist was trying to do and how the work might provide a challenging or reassuring glimpse of the world around us. It was often a deeply enthralling experience. I owe much to Mother, but her patient transmission of her love of art is a treasure beyond calculation.” [7]

GETTING ADVICE

In addition to having a keen eye, David Rockefeller was able to access the best advice possible before buying a work of art.

“Before making a decision to buy any painting of substantial value, we always sought professional advice concerning its authenticity and quality, but the final and determining consideration was invariably whether we both liked it. Among our many mentors, three individuals, all intimately associated with the Museum, stand out: Alfred H. Barr, Jr. [the director of the Museum of Modern Art]; Monroe Wheeler, for many years the Museum’s director of publications and exhibitions; and William S. Rubin, now Director Emeritus of the Department of Painting and Sculpture [at the Museum of Modern Art].” [8]

“While there were many others over the years who helped us in the selection of paintings for our collection, Alfred had the greatest impact.” [9]

“Over a decade or more, Alfred brought to our attention works of high quality. Peggy and I were drawn to the French Impressionists and Postimpressionists, and the first significant painting we bought under Alfred’s tutelage was a beautiful Pierre Bonnard flower painting. This was followed by a Matisse still life and, in 1951, Renior’s stunning nude Gabrielle at the Mirror, for $50,000 [approximately $490,000 in current dollars]. It was our first important Impressionist painting and by far the most expensive. We hung is proudly in our living room in the City, although some of Peggy’s conservative relatives were scandalized at the sight of a nude woman so prominently displayed!” [10]

ART AS AN INVESTMENT

For Rockefeller, the pursuit of the best objects also led to substantial financial rewards.

“The paintings we acquired during the 1950s and 1960s established standards of quality and beauty that I have tried to maintain in my collecting ever since. Some of our earliest purchases would now command prices a hundred times more than what we paid for them, a reflection of their high quality and the boom in the art market that began in the 1980s and continues today. While we never bought paintings as an investment, our art collection has become one of my most valuable assets and represents a significant part of my personal wealth.” [11]

LEGACY PLANNING AND THE NEXT GENERATION

While David Rockefeller’s parents where passionate collectors, as where many of his siblings, the collecting gene did not pass to the next generation.

“Private collections, such as the one Peggy and I have been able to assemble, are, I suspect, a phenomenon that will be less and less possible or perhaps even desirable in the future. In the first place, the supply of great paintings has diminished as many countries now prohibit the export of works which they view as part of their national heritage. Increasingly, masterworks now go to museums, with the result that they rarely enter the art market again. Along with this shortage goes an astronomical price increase for what is available. Secondly, high estate and inheritance taxes make it difficult for collectors to pass on works of art from one generation to another. Thirdly, most people simply do not have the space to house large collections. Nor do they wish to be burdened with the risk of theft or the high cost of insuring valuable items.” [12]

“We have seen a significant generational change in collecting habits among our own children. While they enjoy acquiring works of art on a modest scale, their life-styles, which are quite different from Peggy’s and mine, do not readily allow for an accommodation with many valuable possessions. As a result, they have not continued to anything like the same degree of tradition of art collecting that my parents initiated and that Peggy and I have followed. Over the years, we have often given our children paintings, drawings, or prints for their own homes, but none of them seems eager to go about collecting as seriously as we have.” [13]